Hafez

| Hāfez-e Šīrāzī | |

|---|---|

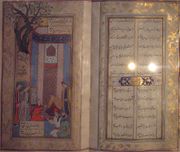

Hafez, detail of an illumination in a Persian manuscript of the Divan of Hafez, 18th century |

|

| Born | c. 1325/26 Shiraz |

| Died | 1389/90 Shiraz |

| Occupation | Poet |

| Nationality | Persian |

| Period | Muzaffarids |

| Genres | Persian poetry, Persian Mysticism, Irfan |

| Literary movement | Poetry, Mysticism, Sufism, Metaphysics, ethics |

|

|

|

Khwāja Šamsu d-Dīn Muḥammad Hāfez-e Šīrāzī (Persian: خواجه شمسالدین محمد حافظ شیرازی), known by his pen name Hāfez (1325/26–1389/90)[1] was a Persian lyric poet. His collected works (Divan) are to be found in the homes of most Iranians, who learn his poems by heart and use them as proverbs and sayings to this day. His life and poems have been the subject of much analysis, commentary and interpretation, and have influenced post-Fourteenth Century Persian writing more than anything else has.[2][3]

The major themes of his ghazals are love, the celebration of wine and intoxication, keeping the sincere faith and exposing the hypocrisy of the religious leaders.

His presence in the lives of Iranians can be felt through Hafez-reading (fāl-e hāfez, Persian: فال حافظ), frequent use of his poems in Persian traditional music, visual art and Persian calligraphy. His tomb in Shiraz is a masterpiece of Iranian architecture and visited often. Adaptations, imitations and translations of Hafez' poems exist in all major languages.

Contents |

Life

Despite his profound effect on Persian life and culture and his enduring popularity and influence, few details of his life are known, and particularly about his early life there is a great deal of more or less mythical anecdote. Some of the early tazkeras (biographical sketches) mentioning Hafez are generally considered unreliable.[4] One early document discussing Hafez' life is the preface of his Divān, which was written by an unknown contemporary of Hafez whose name may have been Moḥammad Golandām.[5] Two of the most highly regarded modern editions of Hafez's Divān are compiled by Moḥammad Qazvini and Qāsem Ḡani (495 ghazals) and by Parviz Natil Khanlari (486 ghazals).[6][7]

Modern scholars generally agree that Hafez was born either in 1315 or 1317, and following an account by Jami, consider 1390 as the year in which he died.[5][8] Supported by patronage from the area’s rulers, from Shah Abu Ishaq, who came to power while Hafez was in his teens, until the rule of Timur Lang (Tamerlane) at the end of his life, he even managed to write under the strictly orthodox Muslim and tyrannical ruler Shah Mubariz ud-Din Muhammad (Mubariz Muzaffar), though his work flourished most under the twenty-seven year reign of Jalal ud-Din Shah Shuja (Shah Shuja).[9] Although no historical evidence of this is available, one source claims that Hāfez briefly fell out of favor with Shah Shuja for mocking inferior poets (Shah Shuja wrote poetry himself and may have taken the comments personally), forcing Hāfez to flee from Shiraz to Isfahan and Yazd.[9] His mausoleum, Hāfezieh, is located in the Musalla Gardens of Shiraz

Legends of Hafez

Many semi-miraculous mythical tales were woven around Hāfez after his death.

- It is said that, by listening to his father's recitations, Hāfez had accomplished the task of learning the Qur'an by heart, at an early age (that is in fact the meaning of the word Hafez). At the same time Hāfez is said to have known by heart, the works of Jalal ad-Din Muhammad Rumi, Saadi, Farid ud-Din and Nezami.

- According to one tradition, before meeting Hajji Zayn al-Attar, Hāfez had been working in a local bakery. Hāfez delivered bread to a wealthy quarter of the town where he saw Shakh-e Nabat, allegedly a woman of great beauty, to whom some of his poems are addressed. In the knowledge that his love for her would not be requited and ravished by her beauty, he allegedly had his first mystic vigil in his desire to realize this union, whereupon, overcome by a being of a surpassing beauty (who identifies himself as an angel), he begins his mystic path of realization, in pursuit of spiritual union with the divine. The obvious Western parallel is that of Dante and Beatrice.

- At age 60 he is said to have begun a Chilla-nashini, a 40-day-and-night vigil by sitting in a circle which he had drawn for himself. On the 40th day, he once again met with Zayn al-Attar on what is known to be their fortieth anniversary and was offered a cup of wine. It was there where he is said to have attained "Cosmic Consciousness". Hāfez hints at this episode in one of his verses where he advises the reader to attain "clarity of wine" by letting it "sit for 40 days".

- In one famous tale, the famed conqueror Tamerlane angrily summoned Hāfez to him to give him an explanation for one of his verses

- اگر آن ترک شیرازی بدستآرد دل مارا

- به خال هندویش بخشم سمرقند و بخارا را

- If that Shirazi Turk would take my heart in hand

- I would remit Samarkand and Bukhārā for his/her Hindu mole

With Samarkand being Timur's capital and Bokhara his kingdom's finest city. "With the blows of my lustrous sword," Timur complained, "I have subjugated most of the habitable globe... to embellish Samarkand and Bokhara, the seats of my government; and you, would sell them for the black mole of some boy in Shiraz!" Hāfez, so the tale goes, bowed deeply and replied "Alas, O Prince, it is this prodigality which is the cause of the misery in which you find me".

So surprised and pleased was Timur with this response that he dismissed Hafez with handsome gifts.[9]

Works and influence

Hafez was well acclaimed throughout the Islamic world during his lifetime, with other Persian poets imitating his work, and offers of patronage from Baghdad and India.[9] Today, he is the most popular poet in Iran; even libraries without the Qur’an contain his Diwan.[6]

Much later, the work of Hāfez would leave a mark on such Western writers as Ralph Waldo Emerson and Goethe. His work was first translated into English in 1771 by William Jones.

Most recently, The Gift: Poems by Hafiz the Great Sufi Master, a collection of poems by Daniel Ladinsky (1999) has been both commercially successful and a source of controversy. Ladinsky claims to speak Persian, though not fluently. In the introduction to the book, he states his work is a "unique portrait is derived from the study of thousands of pages of poems and text attributed to this fourteenth-century master [...] working with hundred-year-old English renderings and translations".[10] The texts he purports to have used include H. Wilberforce Clark's 1891 rendering. He said that he found the Persian originals "remarkably demanding" to translate.[11] Critics such as Murat Nemet-Nejat, a poet, essayist and translator of modern Turkish poetry, have asserted that his translations are in fact Ladinsky's own inventions.[12] The fact that Ladinsky's poems are not a literal representation of Hafez' work was a source of embarrassment for Dalton McGuinty, the Premier of Ontario, when it was discovered that the poem McGuinty had recited from Ladinsky's book at a Nowruz celebration in Toronto in 2009 had no corresponding Persian original. Parvin Loloi has said of Ladinsky's work that "it is hard to see that it has done much for the memory of the Persian poet." [10]

There is no definitive version of his collected works (or Dīvān); editions vary from 573 to 994 poems. In Iran, his collected works have come to be used as an aid to popular divination. Only since the 1940s has a sustained scholarly attempt - by Mas'ud Farzad, Qasim Ghani and others in Iran - been made to authenticate his work, and remove errors introduced by later copyists and censors. However, the reliability of such work has been questioned,[13] and in the words of Hāfez scholar Iraj Bashiri.... "there remains little hope from there (i.e.: Iran) for an authenticated diwan".

Though Hāfez’s poetry is influenced by Islam, he is widely respected by Hindus, Christians and others. The Indian sage of Iranian descent Meher Baba, who syncretized elements of Sufism, Hinduism, Zoroastrianism and Christian mysticism, recited Hāfez's poetry until his dying day.[14] October 12 is celebrated as Hafez Day in Iran.[15]

Interpretation

The question of whether his work is to be interpreted literally, mystically or both, has been a source of concern and contention to western scholars[16]. On the one hand, some of his early readers such as William Jones saw in him a conventional lyricist similar to European love poets such as Petrarch[17]. Others such as Wilberforce Clarke saw him as purely a poet of didactic, ecstatic mysticism in the manner of Rumi, a view which modern scholarship has come to reject [18]. This confusion stems from the fact that, early in Persian literary history, the poetic vocabulary was usurped by mystics who believed that the ineffable could be better expressed in poetry than in prose. In composing poems of mystic content, they imbued every word and image with mystical undertones, thereby causing mysticism and lyricism to essentially converge into a single tradition. As a result, no fourteenth century Persian poet could write a lyrical poem without having a flavor of mysticism forced on it by the poetic vocabulary itself.[19][20]. While some poets, such as Ubayd Zakani, attempted to distance themselves from this fused mystical-lyrical tradition by writing satires, Hafiz embraced the fusion and thrived on it. W.M. Thackston has said of this that Hafiz "sang a rare blend of human and mystic love so balanced...that it is impossible to separate one from the other."[21]

For this reason among others, the history of the translation of Hāfez has been a complicated one, and few translations into western languages have been wholly successful.

One of the figurative gestures for which he is most famous (and which is among the most difficult to translate) is īhām or artful punning. Thus a word such as gowhar which could mean both "essence, truth" and "pearl" would take on both meanings at once as in a phrase such as "a pearl/essential truth which was outside the shell of superficial existence".

Hafez often took advantage of the aforementioned lack of distinction between lyrical, mystical and panegyric writing by using highly intellectualized, elaborate metaphors and images so as to suggest multiple possible meanings. This may be illustrated via a couplet from the beginning of one of Hafez' poems.

Last night, from the cypress branch, the nightingale sang,

In Old Persian tones, the lesson of spiritual stations.

The cypress tree is a symbol both of the beloved and of a regal presence. The nightingale and birdsong evoke the traditional setting for human love. The "lessons of spiritual stations" suggest, obviously, a mystical undertone as well. (Though the word for "spiritual" could also be translated as "intrinsically meaningful.") Therefore, the words could signify at once a prince addressing his devoted followers, a lover courting a beloved and the reception of spiritual wisdom[22].

The Tomb of Hafez

Twenty years after his death, a tomb (the Hafezieh) was erected to honor Hafez in the Musalla Gardens in Shiraz. The current Mausolem was designed by André Godard, French archeologist and architect, in the late 1930s. Inside, Hafez's alabaster tombstone bore one of his poems inscribed upon it.

See also

- List of Persian poets and authors

- Persian literature

- Persian mysticism

References

- Peter Avery, The Collected Lyrics of Hafiz of Shiraz, 603 p. (Archetype, Cambridge, UK, 2007). ISBN 1901383091

Note: This translation is based on Divān-e Hāfez, Volume 1, The Lyrics (Ghazals), edited by Parviz Natel-Khanlari (Tehran, Iran, 1362 AH/1983-4). - E.G. Browne. Literary History of Persia. (Four volumes, 2,256 pages, and twenty-five years in the writing). 1998. ISBN 0-7007-0406-X

- Will Durant, The Reformation. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1957

- Erkinov A. “Manuscripts of the works by classical Persian authors (Hāfiz, Jāmī, Bīdil): Quantitative Analysis of 17th-19th c. Central Asian Copies”. Iran: Questions et connaissances. Actes du IVe Congrès Européen des études iraniennes organisé par la Societas Iranologica Europaea, Paris, 6-10 Septembre 1999. vol. II: Périodes médiévale et moderne. [Cahiers de Studia Iranica. 26], M.Szuppe (ed.). Association pour l`avancement des études iraniennes-Peeters Press. Paris-Leiden, 2002, pp. 213–228.

- Hafez. The Green Sea of Heaven: Fifty ghazals from the Diwan of Hafiz. Trans. Elizabeth T. Gray, Jr. White Cloud Press, 1995 ISBN 1-883991-06-4

- Hafez. The Angels Knocking on the Tavern Door: Thirty Poems of Hafez. Trans. Robert Bly and Leonard Lewisohn. HarperCollins, 2008, p. 69. ISBN 978-0-06-113883-6

- Hafiz, Dikter, translated by Ashk Dahlén, Umeå, 2006. 91-85503-04-5 / 978-91-85503-04-9 (Swedish)

- Hafiz, Divan-i-Hafiz, translated by Henry Wiberforce-Clarke, Ibex Publishers, Inc., 2007. ISBN 0-936347-80-5

- Khorramshahi, Bahaʾ-al-Din (2002). "Hafez II: Life and Times". http://www.iranica.com/articles/hafez-ii. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- Yarshater, Ehsan (2002). "Hafez I: An Overview". http://www.iranica.com/articles/hafez-i. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- Jan Rypka, History of Iranian Literature. Reidel Publishing Company. 1968 OCLC 460598. ISBN 90-277-0143-1

Notes

- ↑ http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/251392/Hafez

- ↑ Yarshater. Accessed 25 July 2010.

- ↑ Hafiz and the Place of Iranian Culture in the World by Aga Khan III, November 9, 1936 London.

- ↑ Lit. Hist. Persia III, pp. 271-73

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Khorramshahi. Accessed 25 July 2010

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Lewisohn, p. 69.

- ↑ Gray, pp. 11-12. Gray notes that Qazvini’s and Gani’s compilation in 1941 relied on the earliest known texts at that time, and that they remarked that none of the four texts they used were related to each other. Since then, she adds, more than fourteen earlier texts have been found, but their relationships to each other have not been studied.

- ↑ Lewisohn, p. 67

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Gray, pp. 2-4.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Loloi, Parvin (2003) Hâfiz, master of Persian poetry: a critical bibliography I B Tauris p58-9 ISBN 1860649238

- ↑ Ladinsky, Daniel The Gift: Poems by Hafez the Great Sufi Master. Penguin p3-4 ISBN 0140195815

- ↑ The Gift: Poems by Hafiz the Great Sufi Master.

- ↑ Michael Hillmann in Rahnema-ye Ketab, 13 (1971), "Kusheshha-ye Jadid dar Shenakht-e Divan-e Sahih-e Hafez"

- ↑ Kalchuri, Bhau: "Meher Prabhu: Lord Meher, The Biography of the Avatar of the Age, Meher Baba", Manifestation, Inc. 1986. p. 6712

- ↑ Hafez’s incomparable position in Iranian culture:October 12 is Hafez Day in Iran By Hossein Kaji, Mehrnews.Tehran Times Opinion Column, Oct. 12, 2006.

- ↑ Schroeder, Eric "The Wild Deer Mathnavi" in The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Vol. 11, No. 2, Special Issue on Oriental Art and Aesthetics (Dec., 1952), p.118

- ↑ Jones, William (1772) "Preface" in Poems, Consisting Chiefly of Translations from the Asiatick Tongues p. iv

- ↑ Davis, Dick: Iranian Studies, Vol. 32, No. 4 (Autumn, 1999), p.587

- ↑ Thackston, Wheeler: "A Millennium of Classical Persian Poetry," Ibex Publishers Inc. 1994, p. ix in "Introduction"

- ↑ Davis, Dick: "On Not Translating Hafez" in The New England Review 25:1-2 [2004]: 310-18

- ↑ Thackston, Wheeler: "A Millennium of Classical Persian Poetry," Ibex Publishers Inc. 1994, p.64

- ↑ Meisami, Julie Scott (May, 1985). "Allegorical Gardens in the Persian Poetic Tradition: Nezami, Rumi, Hafez." International Journal of Middle East Studies 17(2), 229-260

External links

- Online texts and translations

- Fall-e Hafez An online Flash application of his poems.

- Hafez in English at Poems Found in Translation.

- Poems by Hafez English translations of his poetry

- Hafiz, Shams al-Din Muhammad A Biography by Prof. Iraj Bashiri, University of Minnesota

- Hafiz Poems - Translated G.Bell

- Hafez On Love - Divan

- Comprehensive set of scholarly entries about Hafez, on the Encyclopædia Iranica (Columbia University).

- A selection of Love Poems by Hafez

- Radio Programs on Hafez's life and poetry'

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||